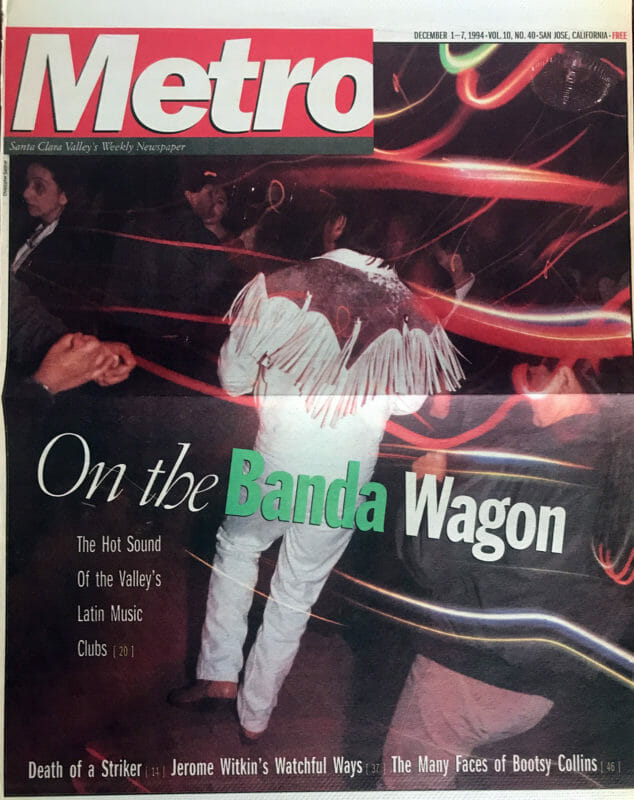

AT ALUM ROCK’S COPA CABANA, four trumpeters unleash a fusillade of notes, and a clarinetist blows furiously in his instrument’s highest registers. Amidst the glorious out-of-tune chaos and reflected mirror images, Banda Capricorn’s tuba player pumps out his oom-pah-pahs to a dance floor packed with flailing knees and elbows.

Blasts of giddy and innocent brass punctuate the singer’s nasal, reverb-heightened Spanish. The trumpeters hustle in unison – hopping back and forth, twisting left and right – while the edges of their un-buttoned vests swing madly.

An army of clicking boots and bouncing Stetson hats commands the floor in front of the musicians. With the fervor of whirling dervishes, some women dancers seem to levitate while their partners use them as human divining rods. They swing under the legs of their male accomplices, their hair spray miraculously holding their bangs rock steady while their bodies hurl through the night.

The true contortionists among them lean back over their partners’ thighs until their spines are parallel with the dance floor, long hair sweeping the wood tiles. It’s a move much more advanced than any from the fox trot or the twist.

The music is banda; the dance is la quebradita – and they dominate the Mexican-American club scene here in the valley and just about everywhere else in the Southwest.

A blend of Latin ballroom, Country & Western two-step, disco and old-fashioned polka, the Mexican musical import banda shows few signs of slowing down after four years of growing acceptance in the United States.

When this rollicking sound and the popular dance that goes with it first tore into the clubs and onto the airwaves at the beginning of the decade, it looked like just another fad. But although some traditionalists still think the craze is a momentary blip on the pop radar screen, banda keeps filling the nightclubs and boosting the ratings of radio stations.

Clearly, banda is here to stay. When a pickup truck or low-slung 1970s Ford tools down the road in the South Bay, it’s often banda that blats out the window. Banda is as ubiquitous as rap in the streets of blue-collar San Jose. The style is unabashedly populist, making it the Mexican equivalent of the country-music boom. And in its exuberance, la quebradita – which means “the little break,” referring to the leaning-back movement of women dancers – echoes country’s wildly popular line dance.

The 100-year-old style, given new life by an infusion of keyboards and electric bass – and often called technobanda – has crossed over from Mexican Pacific Coast immigrants into the Chicano community, first in Southern California and, more recently, in the Santa Clara Valley.

Move Over, Mariachi

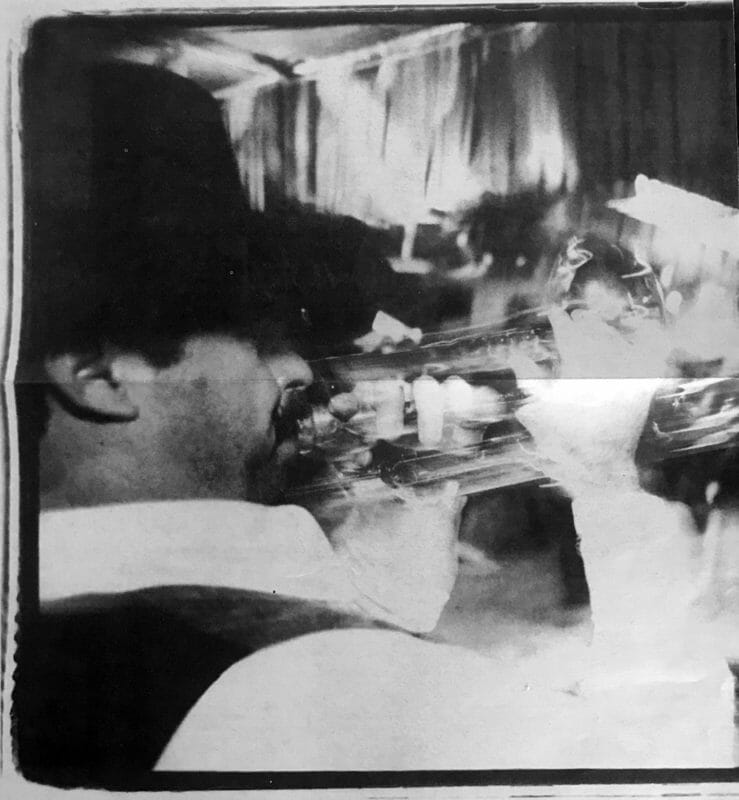

Brass Attack: Banda Capricorn’s trombone player at work

BANDA DIFFERS FROM other Mexican musical genres in its relentless, military-marching-band rhythms and in its instrumentation. While mariachi calls for violins and norteño for an accordion, banda boasts brass and reeds, including clarinets, trumpets, trombones, perhaps a saxophone and a tuba, although many modern bandas have replaced the tuba and clarinet with electric bass and synthesizers. The characteristic drum sound is the roll leading up to a cymbal crash. The 7- to 17-piece outfits play four rhythms: waltz, cumbia (an Afro-Latino dance from Panama and Colombia), son (a complex rhythm from the Mexican state of Veracruz) and corridito (a two-step polka).

Banda lyrics deal with home and family, with dancing and women. Some songs are peppered with double-entendres. At La Tropicana in downtown San Jose, Banda Trueno sings about women who like it long and short – “it” being a mustache. A few songs later, the cantante proclaims, “If your mouth were a green lemon, I’d be sucking, sucking.”

Some banda songs are weightier. Banda Machos’ hit, “Indio Quiere Llorar,” tells of a man rejected by his lover’s wealthy non-Indian family. But make no mistake – rhythm is king in this territory.

“Our banda sings about love and happy things, themes many people may say are stupid, but what people want right now is rhythm, lots of rhythm,” says Pablo Lepe, lead singer for Banda Nayarit Musical.

Like reggae – which has appropriated many American soul hits — banda updates a wide range of songs, from Santana’s “Oye Como Va” to James Brown’s “I Feel Good” to the traditionally American song “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” Banda Brava sings Beatles songs in English to a banda beat. At Copa Cabana, Banda Capricorn played an oom-pah-pah version of Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called to Say I Love You.” Some songs don’t survive the translation well. “They may have been good hits back then, but I still think about it before we can play it,” says Ramon Torres, program director of KNTA-AM (1430), a Spanish-language station in Santa Clara.

Armed with a wide stylistic repertoire, banda is even eroding the traditional musical dominance of mariachi, one sign that it may have real staying power as a genre. Unlike mariachi, banda has turned away from folk-music traditions and immersed itself in contemporary pop.

Promoted by the Mexican government as a symbol of culture, mariachi first became popular in Los Angeles 60 years ago. It focuses on deep emotions – laments, nostalgia or sadness – that are often missing in banda. Nowadays, with more people choosing upbeat bandas to play at their weddings and quinceañeras (coming-out parties for 15-year-old girls), mariachis are losing business; some are even switching to the banda sound.

“Banda is what gets people going,” says Ismael Beltran, president of the 150-member Club Banda Trueno, one of about 25 active fan clubs in San Jose. “The sound of the bass drum really hypes people up. The mariachi is more mellow.”

Francisco Ponce, lead singer of the San Jose-based Mariachi International, remains unconvinced, asserting that banda is nothing more than a fad: “Mariachi has existed, exists and will continue to exist and will never fall from its level in Mexican music.”

So Long, Lambada

ALTHOUGH ITS sound is an attention-getter, banda is not meant just for the ears. It manifests itself in the movement of the quebradita dances as much as it does in the pulse of the brass.

“There’s not a book, there’s not a video where they can show you the quebradita,” says Torres. “You have to learn it with your partner. Everybody has their own way to dance.”

One recent Friday night at Hayward’s Mexicali Rose, a man and woman were swinging together in a pendular arc as if they were sharing a secret. They looked like eager amateurs, lovers in a first embrace. With his leg lodged between hers, the man bent his knee and lowered her back almost all the way to the ground. But in mid-break, they tripped, hopping backward about six steps into one of the large floor speakers.

Unfazed, they laughed off their mishap. One song later, she wrapped her right arm around her guy and let her left arm hang limp as if it were broken. He kept one hand on his ten-gallon hat.

Although quebradita is what the media focused on after banda first crossed the border, it’s only one of several banda dances, which also include the jumping-step brinquito and the horse-step caballito. In the clubs today, not that many dancers are actually attempting full-fledged quebradita.

“It takes a lot of skill, practice and commitment for two people to dance close and not kill each other,” says Susan Cashion, who teaches Latin American dance at Stanford University.

One of Cashion’s students, a fantastic banda dancer, told her he stopped dancing quebradita because the club-going couples had moved away from working together as a unit. Now they dance apart and make up their moves at the last minute, he told her.

Cashion believes that such watering down of the dance forms might aid banda’s mass consumption: “If anyone can do it and bounce around with the rest of the group, like rock & roll, with no skill, just energy, maybe that’s good. Then they don’t have to get with a partner and practice to avoid making fools of themselves when they hit the dance floor.”

Quebradita reminds some of the much-hyped Brazilian lambada, a phenomenon that lasted for only six or seven months, producing two excruciating movie spin-offs. Banda’s already outlived lambada almost eight-fold.

Torres believes that lambada fizzled because it was tied to only one song, albeit a popular one. Some groups tried to mutate the song’s salacious style but couldn’t make a go of it. “Now,” he says, “la quebradita is something easy.”

Rather than learn folklórico classics like “El Tapatío,” Cashion’s students at Stanford want steps they can show off at a club. So, in addition to cumbia, salsa and merengue, Cashion teaches them banda forms. The students enjoy the high-energy excitement of the brinquito and caballito steps, Cashion says. Many Stanford Chicanas, however, reject quebradita because they believe it forces them to relinquish all control to the men who slip them underneath their legs.

“Chicanas had the same reaction to lambada,” Cashion explains. “People liked it, got into the moves, but Chicanas said no, it’s degrading. On this side of the border, they’re a pretty strong voice. In Mexico everyone loves quebradita.”

The Birth of Banda

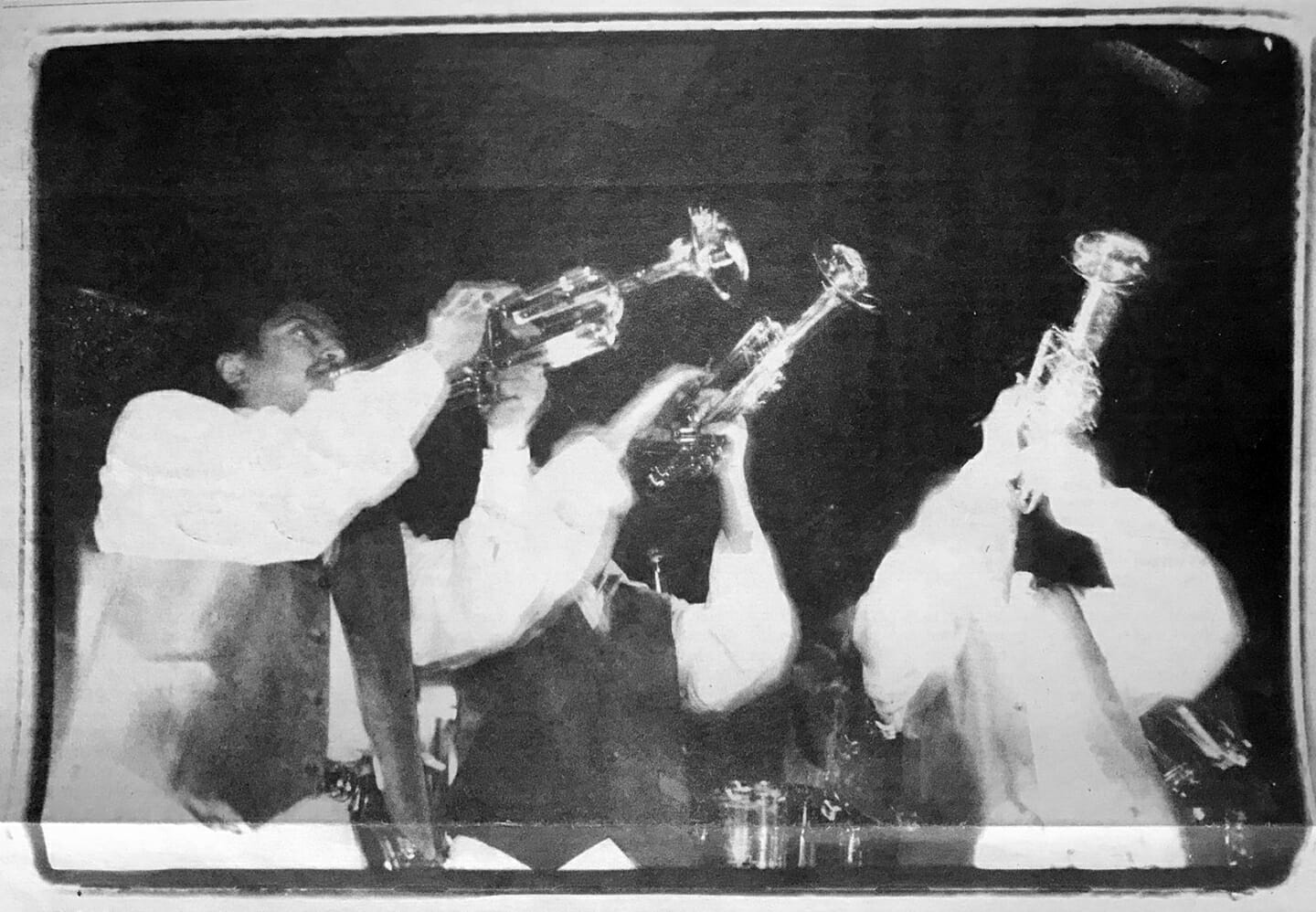

All for One: Members of Banda Capricorn join forces in Alum Rock’s Copa Cabana nightclub. Photo: Christopher Gardner

BANDA’S ROOTS lie in Sinaloa, a state on Mexico’s Pacific coast from which half of Mexico’s agricultural exports originate. When German farmers arrived in the late 19th century, Mexico’s popular town orchestras started to play the instruments of Emperor Maximilian’s military bands.

Bandas still dominate small-town festivals there, escorting religious processions and performing free in plazas throughout Mexico. Banda has even invaded the sophisticated radio stations of Mexico City.

The purely instrumental Banda El Recodo, which hails from Sinaloa, popularized the brassy sound a few decades ago. But the first watershed in a century of relatively little change came six years ago when bandas added singers and synthesizers and replaced their tubas with electric bass to attract a younger crowd. They succeeded wildly. In 1990, Antonio Aguilar’s “Tristes Recuerdos” started a wave that washed first across the western United States and then over other parts of the country.

On Aug. 1, 1992, when Alfredo Rodriguez reformatted Los Angeles radio station KLAX into the all technobanda showcase known as “La Equis,” banda declared to the nation that it had arrived. Rodriguez and his staff members had abandoned demographic studies that lump Latinos of all backgrounds into a single group. Instead, they had visited bars, discos and restaurants to find out what L.A.’s Mexican-Americans were really listening to.

Five months after the change, the station soared to number one on the strength of a multigenerational audience. Its ascent was so rapid that English-language stronghold KLSX examined the Arbitron logs to make sure some of the listeners didn’t accidentally transpose the call letters. Many other Spanish-language stations in the United States followed KLAX’s lead.

San Jose’s KLOK-AM (1170) started playing banda two years ago, when Christopher and Athena Marks bought the ailing station. It had previously eked out dismal ratings playing international music, but with “La Musica de México” it has reached the number-five spot in San Jose. Locally, banda is even more popular than it was last year. “When I answer the phones,” says Joaquin Garza, the station’s 5-lOam disc jockey, “everybody asks me for banda.”

Although banda represents only a fifth of Discoteca Mexico’s stock, it’s the hottest selling kind of music the downtown San Jose record shop carries. And its popularity is growing, says employee José Guzman, who personally prefers Mexican rock groups such as Mana. The current top-three banda cassettes are Tumbando Caña by Banda Maguey, La Experencia Hace La Diferencia by Banda El Recodo and Un Solo Cielo by Banda Sinaloense Los Recoditos.

The leading banda record label is L.A.-based Fonovisa. The company’s biggest release so far is Banda Machos’ Casimira, with at least 300,000 copies sold. Since the SoundTrack sales monitoring system doesn’t track record sales at many mom-and-pop Latino stores, it’s hard to gauge the real success of the records. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that cassettes are frequently counterfeited and sold cheaply at flea markets and small stands outside shopping centers.

‘Quebradita’ Corridor

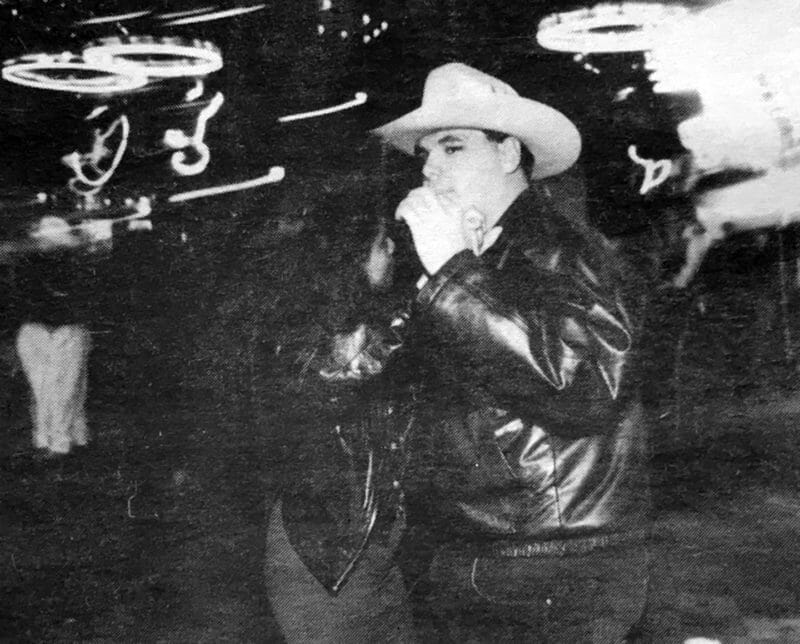

Basic Black: Getting close in downtown San Jose’s La Tropicana. Photo: Christopher Gardner

WITH LATINOS’ numerical dominance increasing throughout the United States, banda will have a fertile field in which to grow. The 1990 census counted 22.3 million Hispanics nationwide, a 53 percent increase since 1980. Latinos are predicted to become California’s majority group by 2040 and the largest group in Los Angeles by 2007.

Banda’s explosion in the United States has been fueled by an immigration corridor stretching from the Pacific Mexican states of Michoacan, Jalisco, Nayarit and Sinaloa to the eastern Washington state fruit orchards. Each region along the immigration corridor has developed its own style of banda music and dance, resulting in a variety of modulated styles. Susan Cashion believes dancers in the Bay Area don’t have the energy of average villagers in a place like Jalisco. Whether due to male villagers’ more physical jobs or simply to the legacy of the charro horsemen, Mexican men are in better shape. Cashion says the villagers there jump harder, drop their partners lower to the ground and support more of the women’s weight than do their Bay Area counterparts.

Here, she says, the laid-back shufflers “come in dressed in beautiful leather jackets with fringes and look the part great. But it’s just not the same energy.” And Mexican banda musicians – especially the well-choreographed horn players – exert more energy than the dancers, she says.

Banda musicians do exult in flash, in Mexico and here. At Hayward’s Mexicali Rose, Banda Vaquero Musical’s five-minute pre-recorded introduction is packed with hype. During a frenetic flurry of laser sounds, a modulated voice introduces each band member as he walks on stage in a fringed white and purple jacket. There is reverb on the reverb. The singer then calls out the names of Mexican states like rap MCs once called out New York boroughs.

Whatever the regional modifications, banda’s overt connection to its Mexican origin is a significant part of its appeal for Mexican-Americans. When some members of Banda Nayarit Musical paused in front of the Fiesta Nightclub before a show, they reflected on why they don their black hats, black pants and black shirts with red tassels arranged in a V.

“Banda is 100 percent Mexican, and I’m 100 percent Mexican – therefore I like it,” says singer Pablo Lepe. “We have to represent our country,” chimes in guitarist Daniel Jimenez.

Outpacing Hip-Hop

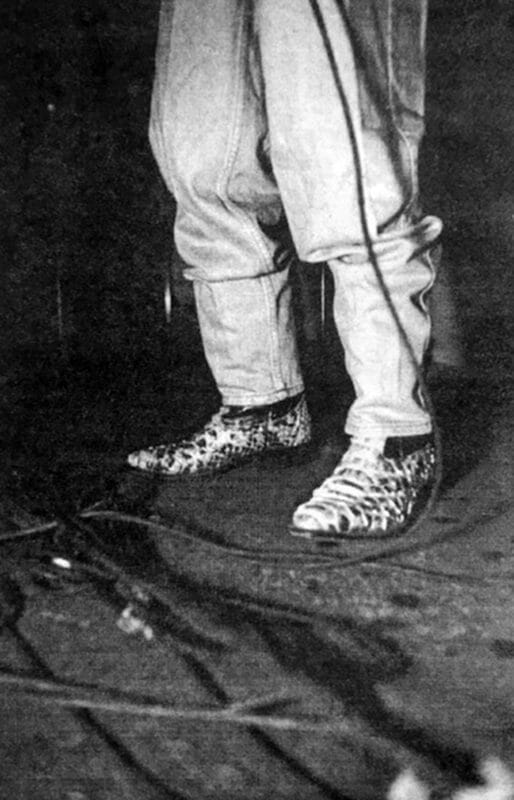

Photo: Christopher Gardner

BANDA IS CLEARLY more than just another lambada in the night, but opinions differ on the current and long-range prospects for the sound in Santa Clara County. Club Banda Trueno’s Beltran says he thinks banda’s popularity is still edging upward. Fiesta Nightclub owner Miguel Sandoval, whose club features banda on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, says the music is remaining at the same high level.

On the other hand, although KNTA’s Torres still plays a lot of banda on his station, he thinks banda’s popularity has diminished in the last three or four months: “They have bandas in almost every nightclub and people are starting to get bored of them.”

A few months may not be the right time frame in which to judge banda; pop critics once thought rap music would just go away too. KLOK’s Garza says tropical music might hit big in the future but that banda will reign as king for at least the next couple of years. Torres speculates that the next wild thing could be accordion-laced norteño if the right group lights a chispa. or spark. But even he acknowledges that banda has permanently worked its way into the ears of the Latino community.

“It’s like if you go to a hamburger place and you’re tired of eating hamburgers, you’ll try a hot dog one of these days,” Torres smiles. “The hamburger will stay there.”

Maybe the best way to tell how long banda will rule is to look at the dances today’s children like. Kids are dancing to banda at home and devouring weekend television variety shows that feature the music. In some local high schools, banda has beat out hip-hop in popularity.

More than 2,000 Latinos in grade school and older have formed banda clubs in San Jose. The groups – each named after a popular banda – are involved in charitable activities like food drives and graffiti paint-outs. Members try to out-quebradita each other in friendly competitions that have replaced gang-banging for many teens.

One recent Sunday at La Tropicana in downtown San Jose, almost a dozen grade-schoolers mixed among the melded adult couples. Two kids in identical blue, red and green shirts – probably brother and sister – clung to each other as they perfected the slower banda techniques. Suave and composed boys with slicked-back hair circulated through the dance floor showing off their brinquito and caballito moves. One 10-year-old with braided hair fingered his hat like a pro.

“Banda’s gonna go off pretty big,” Beltran says. “They thought it would just be around a little while, like lambada. But banda’s got music for all ages.”